July 2024 - In this interview, the technology philanthropist and veteran ICT engineer, Kishor Narang, describes his growing involvement with standardization efforts in India and international bodies. His motivation is to promote energy efficiency, sustainability, and cyber-security in shared digital infrastructure. Kishor discusses India’s ‘leapfrogging’ opportunity and characteristics of the indigenous market that require local strategies to drive IoT and ‘smart’ technology adoption.

Q: Would you begin by introducing yourself?

KN: I have been an electronics design engineer and am currently practicing as a small independent design house (IDH), Narnix Technolabs Pvt. Ltd., based in New Delhi since 1981. Although my experience dates back to the vacuum tube era, nowadays I focus on system architecture and system design problems and projects using much more modern, heterogenous multi-core system on a chip (SoC) technologies. My projects are spread across multiple sectors including automotive, defence and industrial applications. I even contributed to India’s recent space mission to the moon.

I started my career working in a large Indian ICT company many years ago. I grew discontented with the pace of R&D activities in any big organization. That was one of the main reasons for setting up my own design practice in 1981. There followed a period where I got into consulting and after ten-years, I picked up my soldering iron and returned to hands-on electronics design, products, systems and solutions development. Since then, I have been supporting all the multi-national chip companies in developing reference designs for products across different sectors. In many cases, I transfer the solution technology and help my customers’ teams to launch into production.

Q: How has your professional career evolved over the decades to shape what you are working on now?

KN: Initially, I did a lot of work in industrial automation. When market liberalization occurred in India, there was a lot more product design work. Then, around 2007, I got into communications network design to design access networks for buildings wherein I handled systems from different vendors which meant a lot of cabling. There was plenty of work related to smart buildings for access control, building automation, CCTV, intercom, voice, and data communications. All of this was supplied by different vendors and deployed in silos. There was also a very limited focus on standards, protocols, and data models which meant that nobody could share information. This led to a lot of operational complexity and that was the problem statement given to me. That is what led me to design India’s first FTTH-GPON network which made it possible to consolidate all voice, video and data traffic on one fibre and one copper cable (for Electric Power delivery) running through a shaft. It may be noted that this was not a telecommunications service providers’ network but more of an access network providing a 100Mbps superhighway within the buildings. However, there were not many customers at that time for such services as there were no IP-enabled smart devices to plug in.

These kinds of issues that needed harmonization of standards across diverse application domains and infrastructures led me into standardization around 2012. Whatever I have learned from my design practice, I take into the standardization forums and vice versa. Today, standardization is part of my technology philanthropy, and I invest about 70 % of my time and resources in it and am thoroughly enjoying the journey.

Q: How did you choose which bodies and how to get involved in standardization?

KN: It was not so much a matter of choosing because others pulled me into things. Everything began at an IEEE conference where I presented a paper on the standards harmonization imperative for Smart Homes, Smart Buildings & Smart Grid ecosystems. That led to invitations to the IEC and ISO and eventually to the IEC/ISO/ITU joint task force on smart cities. I just try to identify a gap area in standardization from a systems point of view and whichever SDO expresses interest to work on it, I engage with them to take it forward.

Around 2015, I became the founding Chair of the Smart Infrastructure Standardization initiative in India at our National Standards Body BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards). This was the precursor for all the standardization strategy and roadmap for India’s 100 Smart Cities initiative. Rather than jump into point solutions for point problems, we constituted a study group who spent an year and a half to conduct a comprehensive pre-standardization study. This began with a global environmental scan to understand and review the myriad approaches and standards being adopted by Global SDOs to solve problems in the smart infrastructure domain. Through this process, I came across oneM2M and travelled to ETSI Head Quarters in Sophia-Antipolis (France) to learn more about it at an ETSI workshop in 2016.

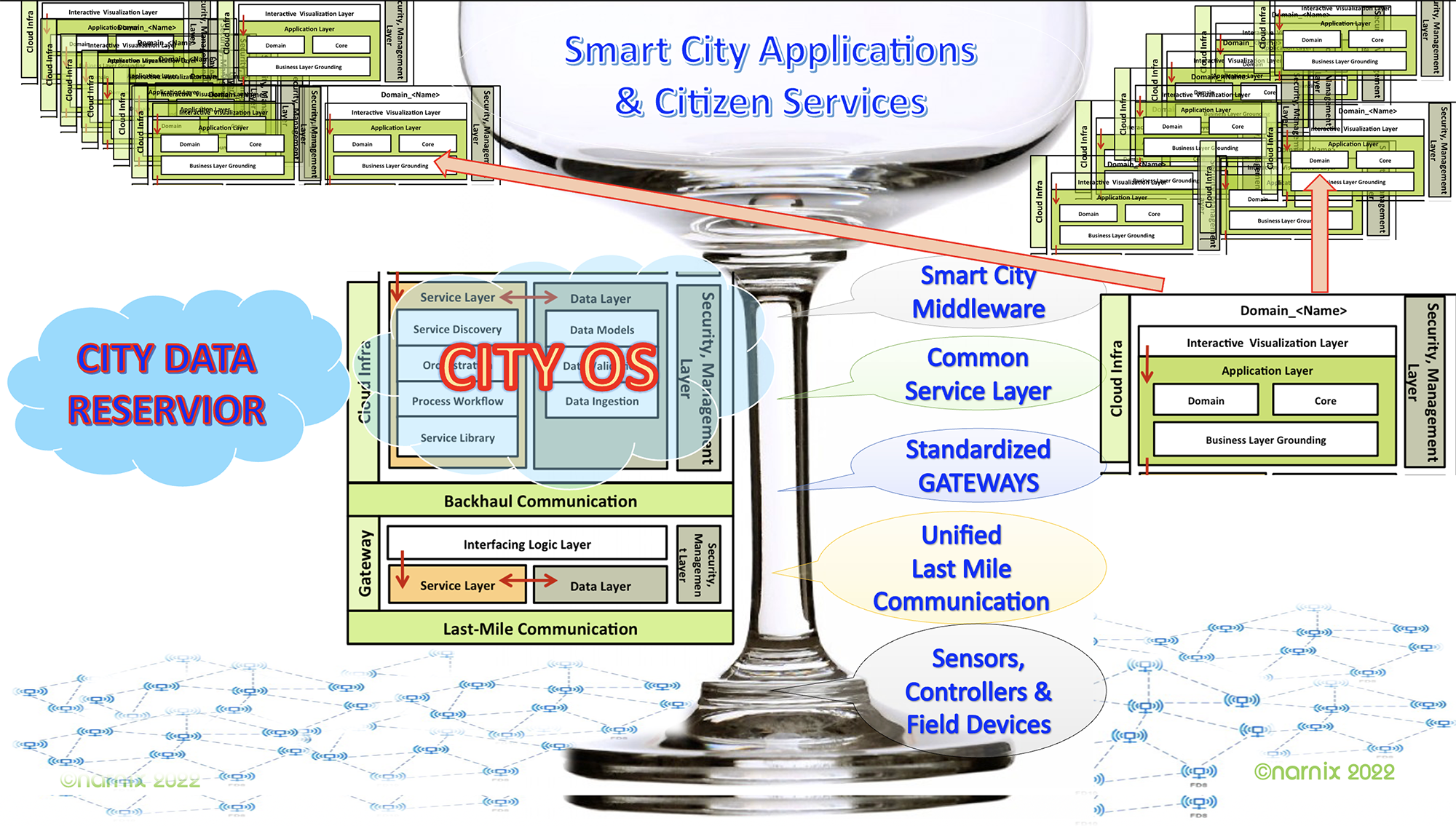

The study initiative led to a report on what elements were best suited to conditions in India. In the process, we came up with a model that we call a classic saucer champagne glass architecture for unified digital infrastructure. The reason for this is that when people talk about interoperability, they use an hourglass model with a narrow neck where everything converges before diverging again. What we realized in our learning is that this neck needs to be long, like the stem of a champagne glass. Also, the top has to be wide because there are a lot of applications coming in.

Figure 1. Classic Saucer Champagne Glass Architecture Model for Unified Digital Infrastructure

oneM2M was one of the core parts of the architecture because it can be deployed in gateways and even in the cloud where all the data comes together. The result is to provide a common interface to expose data to decision making applications.

Q: Would you elaborate on the relevance of standardization in the Indian context?

KN: When we studied smart city deployments in developed markets, we noted that they already had a lot of connected infrastructure. In other words, many of the utility functions could already supply data. All that was required to become a smart city was to connect endpoints, bring data into a cloud system and expose different data sets via dashboards and citizen applications.

That was not the case in India. Our challenge in 2015 was that our utilities were not yet ‘smart’. While India’s electrical utilities were going through the initial phases of digital transformation, other sectors were behind. This gave us a ‘leapfrogging’ opportunity and a way to avoid siloed solutions. This is possible because cities can contain six to eight utilities and several civic service providers. This makes ten or more sets of ICT infrastructures operating concurrently in the same geography. At some point, they need to converge to share information. That was my motivation for targeting a common unified digital infrastructure for all to leverage.

Such an approach would bring down the capital expenditure on digital infrastructure for a city and bring down the operational overhead by avoiding the need for multiple technical teams. It would also reduce the carbon footprint for the digital infrastructure, something that nobody else was talking about in 2015. On top of that, once you have a well architected, common digital infrastructure across the city, it is much easier to make it cyber-resilient. These ideas are now being included in smart city Request for Proposal (RFP) terms, as well as in Global SDOs.

Q: On the topic of smart cities, how has India’s 100 Smart Cities programme progressed?

KN: Initially, the programme had a lot of momentum, broadly grouped under two categories. One included area-based developments, such as a localized congestion pain point, and the other applied to pan-city solutions. Over time, smart cities became blended into other national initiatives such as those addressing water, energy efficiency, renewable energy, e-mobility, solar, AI and quantum missions.

Around 2015, many of my international contacts questioned the scale of the 100 smart cities pilots initiative, noting that a few pilot projects might have sufficed. However, in India, we had four thousand four hundred plus urban local bodies waiting to learn from the pilots. There was a lot of variety in what was being tested which justified covering as many use cases as possible.

Many ideas were tried, some successful and others not. The successful use cases are being carried forward. Now, developments are taking place out of the limelight because we are in a phase of everyday operations. This is an on-going story with a lot more work to be done in relation to technology development and standardization. Hype has died down, work has not.

Q: Returning to the topic of standardization, what role can India’s ICT and systems integration business ecosystems play?

KN: Let me start with this observation. India’s technology companies do not see a business case in standardization. Standardization requires time, energy and resources with a payback that takes multiple years. I view the standardization business model as comprising the following steps – innovation, patenting, promotion of standard essential patents (SEPs), getting innovation in standards, commercialization and finally monetization. This can be a five-to-ten-year cycle for which Indian technology companies lack the patience.

When you study global companies, many are engaged with global SDOs, as well as in industry consortia. You see few Indian companies participate because there is a financial hurdle in terms of membership fees, annual subscriptions, and expenses to attend meetings. That is money invested which could be earning immediate returns elsewhere. Unless standards are made mandatory, technology companies in India do not get involved.

However, standardization is important at the national level. For indigenous technology businesses, there is a hurdle of a few hundred dollars or euros to download international standards documents. That is why the Indian government introduced policies to remove the entry fee for accessing standards. This happens via National standardization bodies in India.

Q: Let us now turn to the IoT industry in India and how it is developing. What do you see as the key market drivers and dynamics?

KN: Before we talk about the IoT in India, let us just think about IoT in general. The problem with IoT is that it stands for a fragmented and heterogeneous ecosystem. All the multi-billion forecasts for the IoT have failed because of a lack of standardization and a lack of interoperability. Everybody develops their proprietary data stack, their own protocols and even their own data models. There is no interoperability or integration across systems. This is true for the world and for India.

The IoT value chain is perhaps the most diverse and complicated value chain of any industry or consortium that exists in the world. In fact, the gold rush to IoT is so pervasive that if you combine much of the value chains of most industry trade associations, standards bodies, the ecosystem partners of trade associations and standards bodies, and then add in the different technology providers feeding those industries, you get close to understanding the scope of the task. In this absolutely heterogeneous scenario, coming up with common harmonized standards is a major hurdle.

Let me explain with a real-world example. India has a goal of deploying 250 million smart meters. Most of our utilities are State owned so they cannot have one end-to-end solution from one vendor. They need something that is technology and vendor agnostic. They need interoperability from the meter to the gateway and onto the software platform and across vendors. For that standardization is very important. That is why the market is suffering – because of the lack of end-to-end standardization.

However, as India progresses towards becoming a connected nation IoT/M2M devices are being utilized by multiple sectors across the subcontinent. The interconnectedness of these IoT systems across industries will play a crucial role in India’s smart city ambitions. To underline the significance of a standardized framework that enables a smarter and more connected Indian ecosystem, India through its Telecommunication Engineering Centre (TEC) under Department of Telecom (DoT), Ministry of Communication have adopted oneM2M specifications/standards as national standards post their transposition by TSDSI. Also, the Centre for Development of Telematics (C-DOT), a research arm of Department of Telecom has also developed a oneM2M based Common Service Platform. And this oneM2M Platform is one of the Core elements of the “Unified Digital Infrastructure” Reference Architecture based on the aforementioned Classic Saucer Champagne Glass Architecture Model.

Q: Are you optimistic that the situation will change?

KN: Yes, I am, and this is something I am working towards with a focus on digital infrastructure. There is a need for common standards that are domain- and use-case agnostic, right from the device layer to the App layer. I am tackling this by looking at standardization gaps and bridging them through appropriate system standards.

An example is some work I started with the LWM2M protocol for device management. LWM2M is an IoT standard but it does not apply to a lot of legacy OT/IT and SCADA systems which have been operating for decades with very limited remote communication capabilities. There is a lot of profiling and time-series data we can capture as and when needed but not before organizations can connect and collect data remotely. I reached out to OMA (the organization responsible for LWM2M standardization) and agreed a solution with them. We had to go through the process to achieve backward compatibility and to ensure that the market benefits from a global solution rather than an India-specific version.

It is important to work globally. In fact, there should be harmonization across SDOs and that is also something I am currently working towards.

Over the longer term, there is an industry challenge that no standardization body seems willing to address. That is the challenge of consuming data from IoT systems. We already have ways of connecting devices, collecting data, mapping data models via interworking proxies and presenting data via APIs. Let us say that you can characterize a connected device via fifty parameters. If that device connects via LoRa or cellular or ZigBee, each vendor’s solution might present some or all fifty parameters. What happens if you design an App for fifty parameters and only receive data for thirty? Is this something we can address via a standardized compliance test or standardized data models? I hope to have something to report on this by the end of this year.

Q: Is this data interoperability challenge something the cloud providers can solve?

KN: Large cloud providers – Amazon, Google, and Microsoft – are in business to do business and not to develop standards. If Amazon has an IoT challenge in its warehouse, for example, there is a gap it will solve. A Walmart would do its own thing. Not unreasonably, each organization will keep the solution in-house for competitive reasons. It is, however, in the interests of (for example) drone manufacturers (for warehouse package delivery) to promote standardization. That way, they can sell their drones and warehouse automation solutions without any changes for any user.

We are expecting standardization from the wrong stakeholders even though they (cloud providers) are beneficiaries of standardization, as Standardized solutions and technologies cost much less than custom-designed solutions.

Q: Is that why large cloud providers, systems integrators and other technology providers offer free or low-cost developer kits?

KN: The large providers do not offer standards in the formal sense so we should not use the ‘standards’ label because it will confuse people. These providers rely on others to bring in a lot of components and plug-in modules which is why they encourage adoption by via educational guides and developer kits. When you look at IoT platforms from the large cloud providers, they are proprietary. Why is oneM2M not there?

All over the world, start-ups are using one of the large providers’ platforms. However, users cannot move easily from one platform to another. When a company wants to move out, that is when they see the cost of moving out. The financial cost is high and the technical cost even higher because it requires a level of technical competence that most organizations lack. Users get locked-in because it is easy to adopt but very costly to move out. And this where standardization of cloud platforms could help users.

Q: Do you have any closing thoughts to add to our discussion?

KN: Yes, I have some feedback for oneM2M. The early work generated a lot of interest, but I feel that oneM2M has lost its focus by trying to do too much. Out of the twelve common service functions in the standard, for example, almost IoT applications require a handful such as Registration, Discovery, Security, Device Management, Application & Service Management, Data Management & Repository and Network Service Exposure. My advice is to focus on those to encourage adoption.

The key takeaway from my standardization journey is about the multiplicity of technologies and their convergence in many new and emerging markets. Many applications, particularly those involving large-scale infrastructure, demand a top-down approach to design starting at the system or system-architecture rather than at the product level. Therefore, the systemic approach in design can define and strengthen the systems approach throughout the technical community to ensure that highly complex market sectors can be properly addressed and supported. Standardization promotes an increased co-operation with many other standards-developing organizations and relevant non-standards bodies on an international level. Further, standardization needs to be inclusive, top down and bottom up; a new hybrid model with a comprehensive systems approach is needed.